HSBC Tower Retrofit London: Carving Floors from a 45-Story Building While It Stands

Imagine standing in London's Canary Wharf, watching architects prepare to remove entire floors from a 45-story office tower—while the building remains occupied. That's the reality facing 8 Canada Square, better known as HSBC Tower, where architect Kohn Pedersen Fox will execute what's being called the world's largest office-to-mixed-use transformation. The £400-800M project doesn't just renovate. It surgically removes sections of the building to create outdoor terraces and fundamentally reimagines what a 20-year-old office tower can become.

The stakes extend far beyond London. As cities from New York to Chicago grapple with obsolete office buildings and mounting pressure to reduce embodied carbon, the HSBC Tower retrofit offers a blueprint—and a warning. The project demonstrates that adaptive reuse can work at unprecedented scale, but only with careful structural assessment and bold architectural vision. For developers and architects working on mid-rise buildings across the U.S., the lessons from this Jenga-style renovation cut straight to the core question: retrofit or rebuild?

What Makes HSBC Tower Retrofit Notable

The numbers tell part of the story. HSBC Tower spans 1.1 million square feet across 45 floors, rising 656 feet above Canary Wharf. When HSBC vacates in 2027 after 25 years as anchor tenant, owner Qatar Investment Authority and Canary Wharf Group will begin a transformation estimated between £400M and £800M. The project will convert purpose-built office space into a mixed-use vertical neighborhood containing offices, residential units, a hotel, and public attractions including restaurants, gardens, and entertainment venues.

But the real story lives in the details. KPF's design carves out massive sections of the upper floors to create a multi-story rooftop terrace visible from Tower Bridge. Additional terraces punctuate the facade at multiple levels, dividing the monolithic tower into distinct zones that will be easier to lease and occupy. The approach solves a fundamental problem with deep-floorplate office buildings: they're terrible for residential conversion because natural light can't penetrate more than 40 feet from the perimeter. By removing floor area rather than adding it, KPF creates outdoor space and visual interest while maintaining structural integrity.

The transformation tackles what urbanist Alexander Morris calls "the long-term challenge"—designing for 60, 80, even 100 years of use rather than the typical 30-year office building lifecycle. Sustainable construction demands this kind of adaptability, especially as environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria reshape real estate investment.

The Engineering Challenge: Removing Floors from a Standing Tower

Removing structural elements from a 45-story building while maintaining its stability requires surgical precision. The Foster + Partners-designed tower was completed in 2002 with a steel-and-glass facade and deep floorplates measuring 184 feet on each side. That dimension creates the residential conversion problem—light would need to travel 92 feet to reach the center of an unmodified floor. But four elevator banks in the central core push leasable space toward the building's perimeter, reducing the actual distance to just 42 feet maximum.

KPF's solution exploits this layout. By carving out sections near the building's edges and creating terraces, they bring outdoor space and natural light closer to what remains of each floor. The multi-story cutout near the top of the tower will become the most visible element on the Canary Wharf skyline, but smaller terraces throughout the building serve a more practical purpose: they divide the tower into leasable sections with distinct identities and uses. This addresses a key challenge with monolithic office buildings—when a major tenant leaves, finding another occupant willing to take 45 floors of identical space proves nearly impossible.

HOK architects explored similar concepts in speculative designs for the same building, proposing divisions into residential, office, hotel, and emerging industry zones. Their research highlighted the structural realities: you can't easily convert deep office floorplates into attractive apartments, but you can create mixed-use buildings where different floor types serve different purposes. The highest floors might become a hotel with spectacular views. Middle floors could house smaller office tenants or serviced apartments. Lower levels bring retail, dining, and public amenities that activate the ground plane.

Compare this to prefabricated facade systems on mid-rise buildings, which often replace existing envelopes without touching interior structure. Both approaches preserve embodied carbon in the building's bones while transforming its skin and function. The difference lies in scale and ambition—HSBC Tower removes structure to add value, while facade retrofit systems enhance performance within existing footprints.

Embodied Carbon: The Retrofit Advantage

Here's what the commercial real estate industry is finally confronting: demolishing a building and constructing a replacement wastes staggering amounts of embodied carbon. Research shows that retrofitting existing buildings saves 50-75% of embodied carbon compared to demolish-and-rebuild scenarios. The foundation, structure, and envelope of a typical building account for over 60% of its embodied carbon—exactly the elements that adaptive reuse preserves.

The math gets worse for new construction advocates. A University of Notre Dame study analyzing over one million Chicago buildings found that new buildings can take 10-80 years to offset the emissions generated during construction, even when they're 30% more energy efficient than average. The United Nations reached a similar conclusion when renovating its New York headquarters—demolition and new construction wouldn't pay back the embodied carbon for 35-70 years. If climate goals target mid-century carbon neutrality, that payback period matters enormously.

London has responded with policy. The Greater London Authority now requires Whole Life Carbon assessments for new developments, forcing developers to account for embodied carbon alongside operational energy. The Royal Institute of British Architects launched a Retrofit First campaign championing building reuse, highlighting that a 20% VAT levy on refurbishments versus 0-5% on new builds creates perverse incentives favoring demolition. As sustainability regulations tighten, these policies will likely spread to other cities.

For HSBC Tower, adaptive reuse makes overwhelming environmental sense. The building's substructure, concrete core, and steel frame remain sound after just 22 years. Replacing cladding, mechanical systems, and interior finishes can achieve modern performance standards without squandering the embodied carbon locked in those structural elements. Projects like The Heritage in New York demonstrate similar principles at mid-rise scale—retrofit the envelope and systems while preserving structural bones.

Lessons for Mid-Rise Building Retrofits

The HSBC Tower project operates at a scale most developers will never encounter. But the principles translate directly to the 5-15 story buildings that dominate U.S. cities. Start with structural assessment. Age and condition of a building's frame often determines retrofit feasibility before architectural concepts even emerge. Buildings from the 1960s-1980s frequently used durable concrete or steel construction that remains structurally sound even as mechanical systems and facades fail.

Deep floorplates present the same challenge at any height. A 15-story office building with 100-foot-wide floors faces identical daylighting constraints as its 45-story counterpart. Solutions include selective demolition to create lightwells or atriums, mixed-use programming that places offices (which tolerate deeper spaces) in building cores, or facade modifications that bring more natural light deeper into floorplates. NYC facade retrofit projects frequently combine envelope replacement with interior reconfiguration for exactly these reasons.

Ceiling heights matter enormously. Buildings constructed with generous floor-to-ceiling dimensions (10-12 feet) offer more flexibility for residential conversion, new mechanical systems, and improved acoustics. Structures built with minimal clearances (8-9 feet) constrain what's possible without expensive structural modifications. This explains why some 1960s office buildings retrofit beautifully while others struggle—the original design assumptions about future adaptability turn out to be self-fulfilling.

Occupied building methodology becomes critical when tenants can't relocate during construction. HSBC Tower benefits from a complete vacancy in 2027, allowing contractors full building access. Most retrofits can't afford that luxury. Occupied building retrofit techniques minimize disruption through phased construction, prefabricated components that reduce on-site work, and interior installation methods that avoid exterior scaffolding and the attendant noise, dust, and visual impact.

ESG drivers are reshaping retrofit economics. Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards in markets like New York require facade upgrades for buildings that can't meet performance targets. Green financing offers better mortgage rates for energy-efficient buildings. Investors increasingly factor embodied carbon into acquisition decisions. These forces create financial incentives that align with environmental imperatives, making retrofit projects economically viable where they might have seemed marginal five years ago.

Dextall's Approach to Occupied Building Retrofits

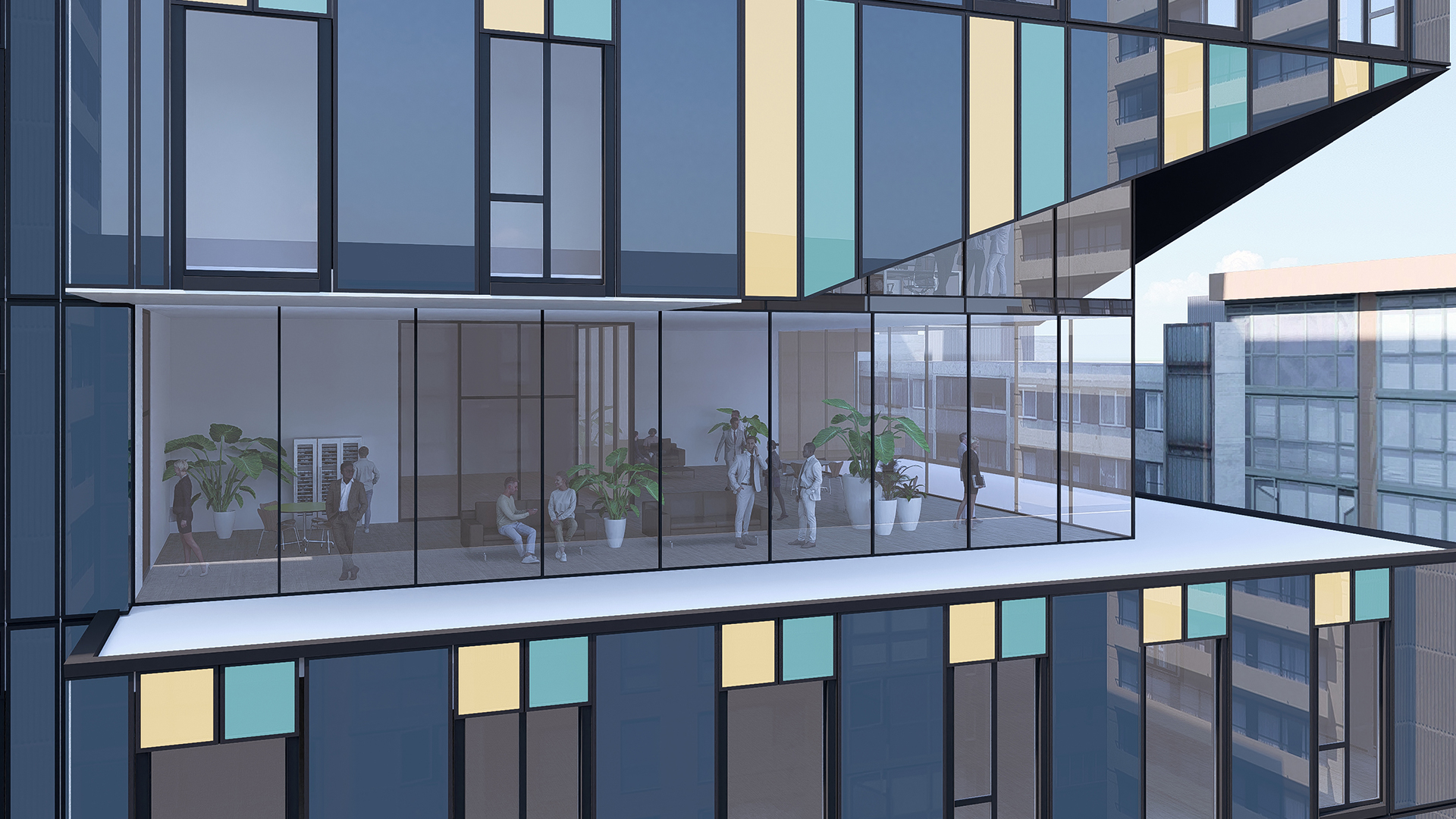

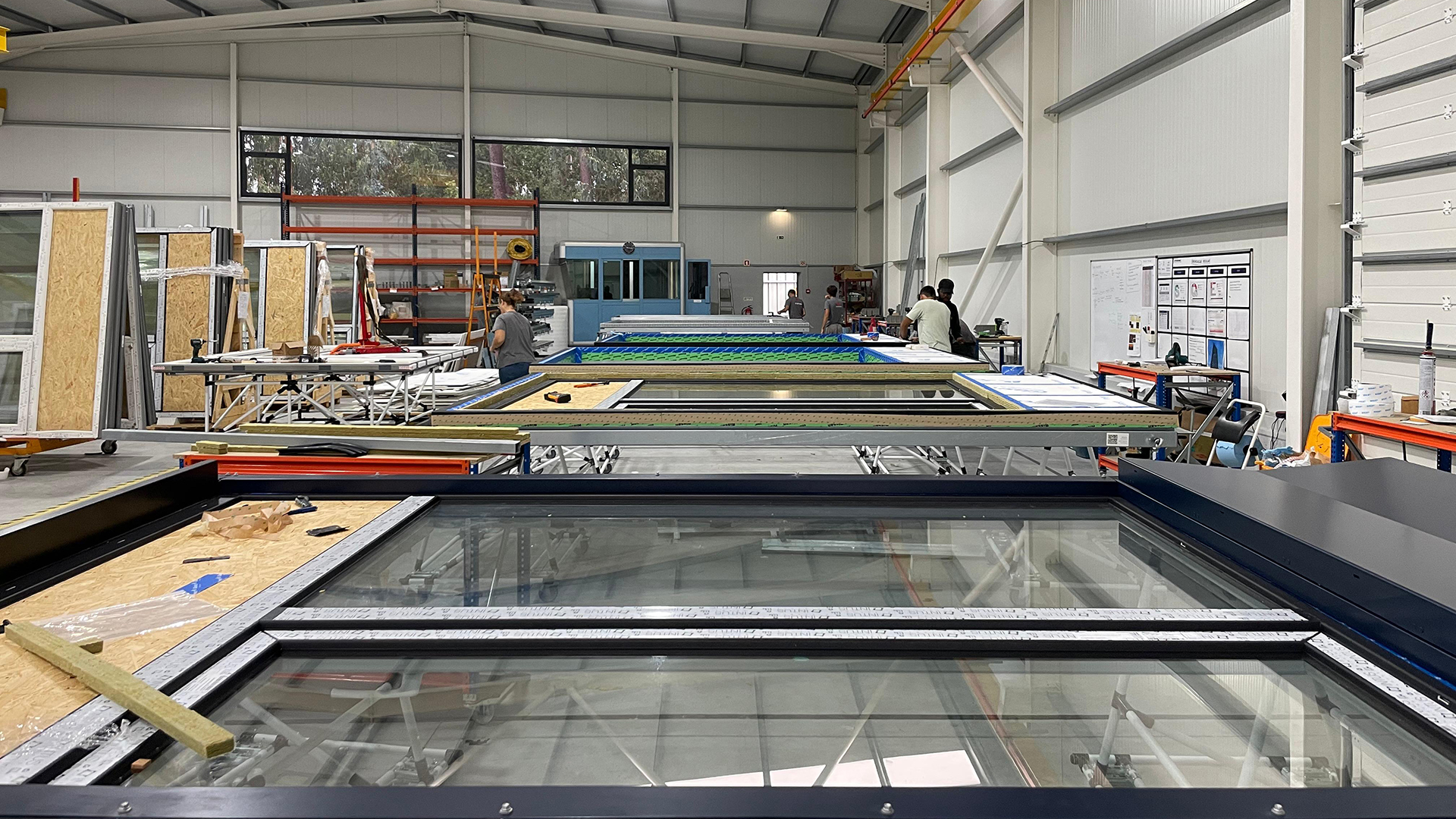

While KPF carves floors from HSBC Tower's exterior, Dextall's approach to occupied building retrofits works from the inside out. The Heritage project at 1660 Madison Avenue in Harlem demonstrates interior installation methodology at mid-rise scale. Residents remain in their apartments while D Wall® prefabricated panels are installed from inside the building envelope, eliminating the need for exterior scaffolding that would disrupt the neighborhood and dramatically increase costs.

The methodology difference matters. Exterior scaffold systems can add 20-30% to project budgets on mid-rise buildings and extend timelines by months. They create visual blight in residential neighborhoods and require complex logistics for material delivery in dense urban settings. Interior installation avoids these challenges while maintaining factory-controlled quality standards for panel fabrication. Each panel arrives with windows, cladding, and insulation pre-installed, reducing on-site labor by up to 87% compared to traditional stick-built construction.

The NJPAC project in Newark shows similar principles applied to a mixed-use development. Factory fabrication parallel to site work compresses overall timelines. Precision manufacturing eliminates weather delays and quality inconsistencies that plague field construction. Digital coordination through Dextall Studio ensures panels integrate seamlessly with existing structure and new interior layouts.

Where HSBC Tower and Dextall converge is in the recognition that embodied carbon preservation matters. HSBC keeps its concrete core and steel structure. Heritage projects preserve load-bearing walls and foundations. Both replace energy-wasting building envelopes with modern, high-performance alternatives. Both achieve dramatic improvements in operational efficiency without the carbon penalty of demolition and reconstruction.

The scalability question becomes crucial. A £400-800M project with international architecture stars makes headlines. But affordable housing developments in Queens and the Bronx face the same core challenges—obsolete envelopes, occupied buildings, tight budgets, aggressive timelines, and mounting pressure to reduce carbon emissions. Prefabricated facade systems bring factory efficiency to projects where margin pressure doesn't allow for experimental engineering. They make adaptive reuse financially viable at scales where custom solutions would prove prohibitive.

Key Takeaways for Developers and Architects

The HSBC Tower retrofit crystallizes several principles that apply across building types and scales. First, structural assessment comes before architectural vision. Understanding what elements of an existing building remain sound versus what requires replacement determines whether retrofit makes economic and environmental sense. Waiting until design development to discover structural inadequacies wastes time and money.

Second, mixed-use programming expands retrofit possibilities. Single-use office buildings struggle when their original tenant profile becomes obsolete. Buildings that can accommodate offices, residential, retail, and public uses prove more resilient to market shifts. This applies equally to 45-story towers and 12-story mid-rise structures. Flexible facade systems support this kind of programmatic diversity by allowing different performance characteristics on different floors.

Third, embodied carbon calculations need to drive early decision-making rather than serving as retroactive justification. Whole Life Carbon assessment reveals whether retrofit or replacement produces better environmental outcomes over 50-60 year timeframes. In the vast majority of cases, retrofit wins—but only if structural elements warrant preservation and operational efficiency can reach acceptable standards.

Fourth, occupied building techniques unlock retrofit projects that would otherwise require tenant relocation. Methods that minimize disruption make economic sense even when they cost slightly more than vacant building renovations, because avoided vacancy losses typically exceed any construction premium. Prefabrication, interior installation, and phased construction all contribute to keeping buildings operational during transformation.

Finally, policy and finance are converging to favor retrofit over demolition. ESG investing, Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards, embodied carbon regulations, and green financing create ecosystem pressures that reshape project economics. Developers and building owners who anticipate these trends position themselves advantageously. Those who cling to demolish-and-rebuild models will find capital increasingly difficult to secure and projects increasingly difficult to permit.

FAQ

How does building retrofit reduce embodied carbon compared to new construction?

Building retrofit preserves the foundation, structural frame, and often the building core—elements that account for 60-75% of a building's total embodied carbon. When you demolish and rebuild, you waste all that carbon and emit additional carbon during demolition and new construction. Research consistently shows retrofits save 50-75% of embodied carbon versus new construction, even when the new building is significantly more energy efficient. The carbon payback period for new construction typically ranges from 10-80 years depending on building type and location, which makes retrofit the clear winner when climate goals target mid-century.

What are the main structural challenges when retrofitting large office buildings?

Deep floorplates present the biggest challenge. Office buildings often measure 60-100 feet from exterior wall to core, making natural daylighting impossible for residential use. Solutions include carving out sections to create lightwells, limiting residential to perimeter zones, or maintaining office use in deeper areas. Ceiling heights matter enormously—buildings with generous clearances (10-12 feet) accommodate modern mechanical systems and residential standards more easily than those built with minimal heights. The age and condition of structural elements determines whether retrofit makes sense economically. Concrete deterioration, steel corrosion, and foundation settlement can make preservation more expensive than replacement.

Can prefabricated facade systems work for occupied building retrofits?

Prefabricated facade systems excel at occupied building retrofits when designed for interior installation. The methodology eliminates exterior scaffolding, dramatically reducing neighborhood disruption and often cutting 20-30% from project budgets. Panels arrive with windows, insulation, and cladding pre-installed, minimizing on-site labor and weather-related delays. Factory fabrication parallel to site preparation compresses overall timelines. The key is coordination—panels must integrate precisely with existing structure, which requires accurate field measurements and digital modeling. When executed properly, prefab systems deliver factory quality at field-construction speeds, making them ideal for urban retrofit projects where access and logistics create bottlenecks.

What is the typical timeline for a major retrofit vs demolish-and-rebuild?

Timelines vary enormously based on building size, complexity, and regulatory environment. For a mid-rise building (8-15 stories), facade retrofit with mechanical system upgrades typically requires 12-18 months. Demolition and reconstruction of an equivalent building spans 24-36 months. The difference compounds when you factor in permitting—retrofit projects often qualify for expedited approval under existing building codes, while new construction faces full review. Occupied building retrofits add complexity but can proceed in phases, allowing portions of the building to remain operational throughout. Prefabricated systems reduce retrofit timelines by 30-50% compared to stick-built methods because factory fabrication happens parallel to site preparation.

How does Dextall's interior installation method differ from traditional exterior retrofit?

Traditional exterior retrofit requires scaffolding that surrounds the entire building, creating visual impact, neighborhood disruption, and significant cost. Dextall's interior installation works from inside the existing building envelope, eliminating scaffold requirements. Crews access each unit or floor from interior, remove existing facade elements, and install new prefabricated panels from inside. This approach dramatically reduces disruption for occupied buildings—residents or tenants experience renovation more like interior work than external construction. The method works particularly well in dense urban settings where sidewalk and street access is limited. Because panels are fully fabricated in factory-controlled environments, quality remains consistent regardless of weather conditions during installation. The tradeoff is more complex coordination with building operations, but for occupied retrofits, the benefits far outweigh coordination challenges.

Disclaimer

Dextall is not involved in the HSBC Tower retrofit project. This article analyzes publicly available information about KPF's design and Canary Wharf Group's transformation plans to explore how principles from large-scale adaptive reuse projects can inform mid-rise construction strategies in the U.S. market. For questions about the HSBC Tower project, contact Canary Wharf Group or KPF. For information about Dextall's prefabricated building envelope solutions and retrofit capabilities, visit dextall.com.

Images featured in this article depict Dextall's projects and are used for illustrative purposes only.

.jpeg)

-Compliance-for-NYC-Multifamily-%26-Co-Op-Facades.jpg)

_format(webp).avif)

_format(webp)%20(6).avif)

_format(webp)%20(5).avif)

_format(webp)%20(4).avif)

_format(webp)%20(2).avif)

_format(webp)%20(3).avif)

.avif)

_format(webp)%20(2).avif)