Hudson Mosaic NYC: When a Pritzker Prize Firm Designs Affordable Housing, Everything Changes

The Pritzker Architecture Prize is often called the "Nobel for architects." Its laureates typically design museums, stadiums, corporate headquarters—buildings with no ceiling on budgets. So when Swiss firm Herzog & de Meuron—creators of London's Tate Modern, Beijing's Bird's Nest, and New York's 56 Leonard—takes on 100% affordable housing on a vacant lot in the West Village, it's more than architectural news. It's a signal that the paradigm has shifted.

Hudson Mosaic—a 35-story tower at 388 Hudson Street in Manhattan—will become New York City's first project combining affordable housing with a full-scale NYC Parks recreation center under one roof. Approximately 280 apartments through the Housing Connect program, a six-lane pool, a regulation basketball court with running track, a media lab—all in one of Manhattan's most expensive neighborhoods. The project was announced in December 2025, and it's already redefining what public housing can look like in the 21st century.

What Makes Hudson Mosaic Notable

Start with a fact that surprises even seasoned developers: never before has New York City combined affordable housing with a Parks Department recreation center in a single building. Separately—yes, dozens of times. Together—never. Hudson Mosaic breaks that precedent. The recreation center occupies the lower floors with a separate entrance and lobby, while the residential tower rises above.

The development team—Camber Property Group, Services for the UnderServed (S:US), and Essence Development—was selected through HPD's (Department of Housing Preservation and Development) competitive review process. At least 15% of units are reserved for formerly homeless New Yorkers with access to clinical and social services from S:US. The rest are distributed through the Housing Connect lottery for families and individuals across income levels. This approach creates a vertical community rather than an isolated "project for the poor"—and that distinction matters.

The recreation center deserves its own attention. A six-lane indoor pool with large windows facing JJ Walker Park. A regulation-size basketball court with a running track and bleacher seating. Cardio and strength rooms. A media lab. Flexible multipurpose spaces for dance, youth, and afterschool programs. Permanent public artworks commissioned through the Percent for Art program. All of it free to city residents.

Design Excellence Meets Contextual Sensitivity

Herzog & de Meuron are known for making every project look different. There's no "signature style"—there's a response to a specific place. For Hudson Mosaic, the place demands brick. The West Village is a neighborhood defined by brownstone and red brick buildings from the 19th and 20th centuries, and the trapezoidal tower responds to this context with a varied brick facade. But this isn't imitation. Cubic window units that wrap around the building's corners create a rhythm simultaneously evoking traditional masonry and looking thoroughly contemporary.

The trapezoidal form isn't an aesthetic whim. It minimizes shadows on neighboring streets and JJ Walker Park, meeting NYC's strict insolation requirements. Simultaneously, this geometry creates non-standard apartment layouts with bay windows on the north-south elevations—a detail rarely found in affordable housing. The podium is topped by a landscaped terrace for residents, which together with green roofs creates a micro-ecosystem within dense urban fabric.

Curtis + Ginsberg Architects serve as architect of record, bringing decades of housing expertise. This is an important nuance: Herzog & de Meuron set the architectural vision while Curtis + Ginsberg handle technical execution, code compliance, and coordination with building systems. This pairing—star firm plus local expert—is becoming an increasingly common model for complex public projects.

Passive House and Energy Performance: Not Luxury, Standard

The residential portion of Hudson Mosaic targets Passive House certification. The recreation center targets LEED Gold. This dual strategy reflects reality: certifying a pool and gymnasium to Passive House is challenging due to specific ventilation and humidity requirements, making LEED Gold a more practical path for community spaces.

The entire building is all-electric. No natural gas. Rooftop solar panels, backup power systems for extreme weather events, green roofs. These solutions don't just reduce operating costs for residents—they ensure compliance with Local Law 97, which penalizes buildings for excessive carbon emissions. For affordable housing where margins are already minimal, LL97 fines could be fatal. The Passive House approach transforms a potential risk into a competitive advantage.

Numbers from comparable projects confirm the logic. Sendero Verde—a 709-unit Passive House in East Harlem—demonstrated approximately 50% energy reduction compared to typical NYC construction. For low-income families, $50-150 in monthly utility savings represents a significant share of household budgets. Hudson Mosaic scales this approach in the West Village context, where an energy-efficient building envelope becomes a critical element of the project's financial sustainability.

From Vacant Lot to Community Asset: Context and Process

The 388 Hudson Street site has a long and complex backstory. The land belongs to DEP (Department of Environmental Protection)—beneath it runs the Third Water Tunnel shaft, one of the largest infrastructure projects in New York City's history. The southern portion of the site remains closed to development, providing permanent emergency access to the tunnel below. That area will become Hudson Houston Plaza—0.26 acres of public space designed by Matthews Nielsen Landscape Architects.

The commitment to build affordable housing on this site emerged from the SoHo/NoHo Neighborhood Plan approved by the City Council in December 2021. Community Board 2—one of the worst-performing districts in the city for new housing production—had gone decades without adding significant units. The result: the district became one of the most expensive in the city. HPD released the RFP (Request for Proposals) for the site in February 2025, and the development team was selected in December 2025.

HPD conducted extensive community engagement: presentations to Manhattan Community Board 2, outreach to local organizations, tabling events, online and in-person workshops. Over 500 questionnaire responses shaped the Community Visioning Report that defined priorities—100% affordable housing and recreational opportunities. A separate but related issue involves the Tony Dapolito Recreation Center across the street. Built in 1908, the center has been progressively closed since 2019—first the outdoor pool, then the entire building during the COVID pandemic—and never reopened due to severe structural problems. It houses a 170-foot Keith Haring mural from 1987—an icon of the Village's LGBTQ+ community. The city allocated $51.8 million in the FY2026 budget for the center's future, though whether these funds will go toward demolition and reconstruction or restoration remains hotly contested. The recreation center within Hudson Mosaic is intended to partially replace Tony Dapolito's functions—but the debate is far from settled.

Dextall's Approach to Affordable Housing Construction

Hudson Mosaic is currently in the approvals and financing stage. Construction hasn't begun, and specific building systems haven't been officially announced. But the principles embedded in the project—Passive House standards, all-electric systems, high-performance envelope—define the class of solutions required for delivery.

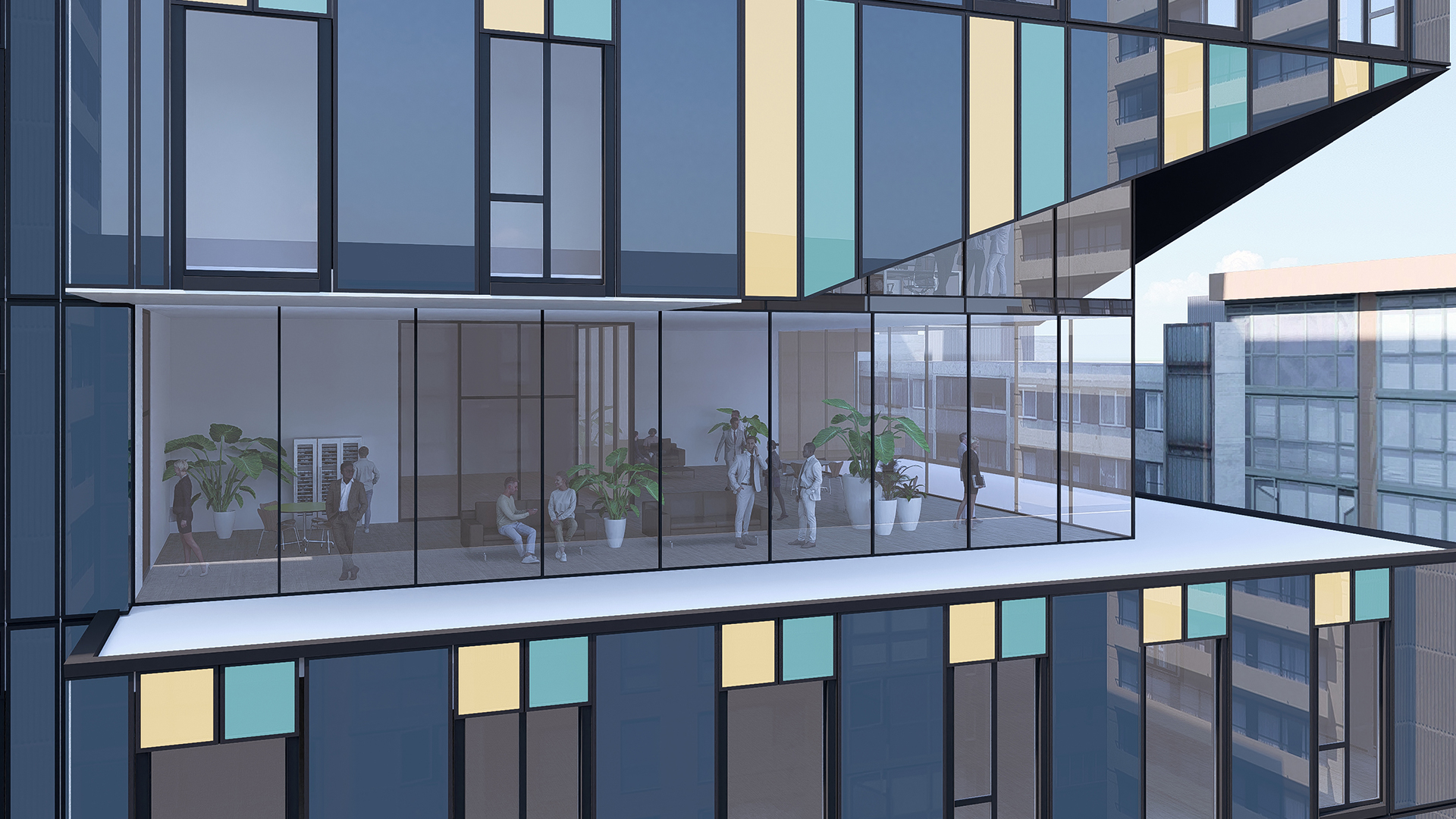

Dextall's projects in New York operate in exactly this segment. Alafia in Brooklyn is a Passive House project where D Wall® prefabricated panels deliver the airtightness and thermal performance required for certification. The Heritage at 1660 Madison Avenue demonstrates retrofit of occupied affordable housing—where residents remain in their apartments during facade system replacement. Carmen Villegas Apartments in the Bronx integrate solar panels with the facade system—an approach Hudson Mosaic also plans to employ.

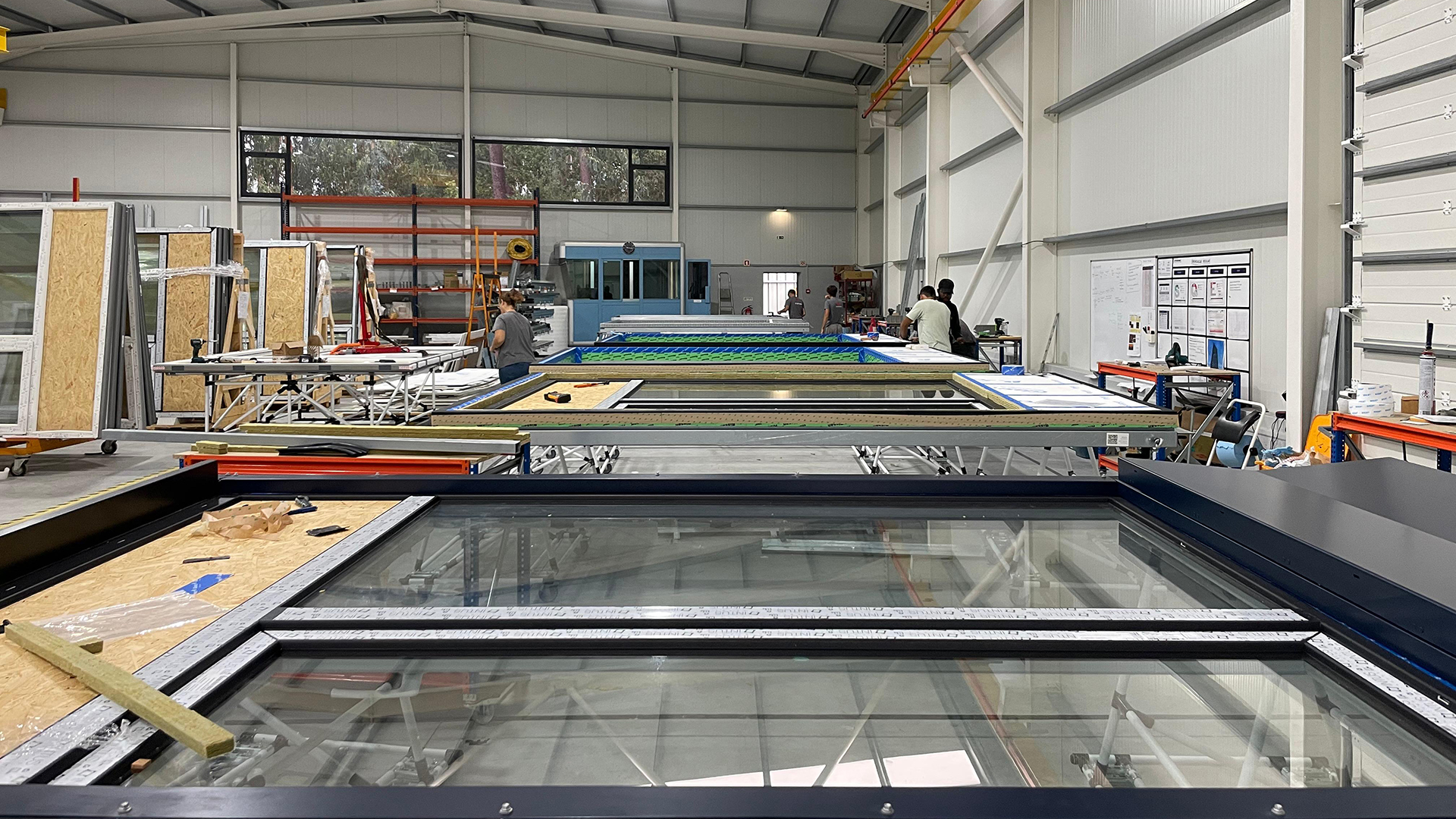

Why is factory manufacturing of panels critical for Passive House? The standard requires airtightness of ≤0.6 air changes per hour at 50 pascals pressure. Achieving this on a construction site, where rain, wind, and temperature fluctuations affect sealing quality, is extraordinarily difficult. Factory environments eliminate these variables. Each panel undergoes quality control before installation rather than after, when corrections cost ten times more.

The NJPAC project in Newark—a 25-story mixed-use tower—demonstrates the scalability of this approach. Parallel panel fabrication and on-site construction compress overall timelines by 30-50%. For affordable housing where carrying costs consume margins monthly and construction delays mean deferred rental income, this time difference isn't just convenience. It's a question of financial viability.

Dextall Studio provides digital coordination between architectural design and manufacturing—transforming schematic designs into detailed fabrication drawings in days instead of months. For projects with complex facades like Hudson Mosaic's varied brick pattern, this coordination determines the difference between theoretically possible and practically achievable.

Key Takeaways for Developers and Architects

Hudson Mosaic crystallizes several principles that extend far beyond a single project in the West Village.

First, star architects and affordable housing are not an oxymoron. When Herzog & de Meuron invest their brand in affordable housing, it changes perception of the entire category. Public housing doesn't have to look cheap. Architectural quality attracts community support, eases ULURP approvals, and draws better contractors. This dynamic works at any scale—from a 35-story tower to an 8-story mid-rise project in Queens or the Bronx.

Second, Passive House and affordability are compatible when financing is structured correctly. NYSERDA grants, federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credits, green financing—these instruments cover the upfront premium, which for experienced teams runs 0-5% of the total budget. Meanwhile, operational savings for residents accumulate over decades. Thirty-year affordability restrictions common in HPD projects mean buildings must perform efficiently not just today but through the 2050s, when climate impacts intensify and energy prices will likely rise.

Third, co-locating uses—affordable housing with a recreation center, school, or clinic—creates stronger community assets than single-function buildings. Sendero Verde combined housing with DREAM Charter School and a Mount Sinai clinic. Hudson Mosaic pairs it with a Parks rec center. These combinations generate broader community support and ensure financial sustainability through diversified programming.

Fourth, Local Law 97 creates market conditions where high-performance facade systems aren't optional—they're mandatory. Buildings that fail to meet standards face penalties that can reach millions of dollars annually. Prefabricated panel systems achieve required performance without compromising budgets or timelines—and this advantage becomes increasingly decisive as enforcement deadlines approach.

Finally, community engagement isn't a formality—it's the foundation. Over 500 responses to HPD's questionnaire, workshops, presentations to the Community Board—this process didn't just legitimize the project. It defined its program. The recreation center, affordable housing, support for homeless residents—all directly respond to community wishes. For developers working in dense urban neighborhoods where NIMBYism can kill any project, this upstream engagement represents the most effective investment possible.

FAQ

Why is Passive House certification critical for affordable housing?

Passive House delivers 40-60% energy reduction compared to typical construction. For low-income families, this translates to $50-150 in monthly savings—a significant share of household budgets. Beyond financial benefits, Passive House ensures stable temperatures, eliminates drafts, provides constant filtered ventilation, and improves sound insulation. These factors directly impact resident health, particularly for children, elderly residents, and those with respiratory conditions. For affordable housing, Passive House isn't a premium option—it's a tool for reducing overall housing cost burden.

How does prefabrication help achieve Passive House standards in new construction?

Passive House requires airtightness of ≤0.6 air changes per hour—a level extraordinarily difficult to achieve through traditional on-site construction. Prefabricated facade systems move critical operations into controlled factory environments where temperature, humidity, and sealing quality are constantly monitored. Windows are installed with precise integration into the airtight layer. Each panel undergoes quality control before shipping. Parallel panel fabrication and foundation work compress overall timelines by 30-50%, which is critical for affordable housing projects with tight budgets.

What role does Local Law 97 play in building system choices for new NYC housing?

Local Law 97 sets carbon emission limits for buildings over 25,000 square feet. Buildings exceeding limits face penalties—potentially millions of dollars annually. For new affordable housing projects where margins are minimal, these fines could be fatal. High-performance facade systems with low thermal conductivity, airtight connections, and integrated windows ensure compliance without expensive compensatory measures. All-electric systems combined with solar panels further reduce a building's carbon footprint.

Can affordable housing achieve design excellence without premium pricing?

Hudson Mosaic proves it can—but this requires specific conditions. First, star architects sometimes work on affordable housing at reduced fees, viewing it as a social contribution and portfolio project. Second, prefabricated panel systems enable complex facade patterns without proportional cost increases, since variation is achieved through digital design and automated manufacturing rather than on-site manual labor. Third, public financing—HPD, NYSERDA, federal tax credits—covers costs unavailable to private-market developers.

How does Dextall's approach differ from traditional affordable housing construction?

Dextall's approach centers on factory-controlled manufacturing of facade panels where windows, insulation, and cladding are installed before shipping to the construction site. This eliminates weather dependency, ensures consistent quality, and reduces on-site labor requirements by up to 87%. For occupied building retrofits, interior installation methodology eliminates exterior scaffolding, cutting budgets by 20-30%. Digital coordination through Dextall Studio transforms months of design into days, enabling parallel work at the factory and construction site. For affordable housing, these speed and quality advantages directly improve project economics.

Disclaimer

Dextall is not involved in the Hudson Mosaic project. This article analyzes publicly available information about Herzog & de Meuron's design and the development team's plans to explore how principles from large-scale affordable Passive House projects can inform mid-rise housing strategies in the U.S. market. For questions about the Hudson Mosaic project, contact HPD, Camber Property Group, or Herzog & de Meuron. For information about Dextall's prefabricated building envelope solutions and energy-efficient affordable housing capabilities, visit dextall.com.

Images featured in this article depict Dextall's projects and are used for illustrative purposes only.

Sources

- NYC HPD Official Announcement — Hudson Mosaic at 388 Hudson Street

- Herzog & de Meuron — Hudson Mosaic Project Page

- The Architect's Newspaper — Herzog & de Meuron to Design Mixed-Use Tower in Greenwich Village

- Dezeen — Herzog & de Meuron and Curtis + Ginsberg Design Hudson Mosaic in New York City

- New York YIMBY — New Renderings Revealed for Hudson Mosaic at 388 Hudson Street

- Services for the UnderServed (S:US) — Hudson Mosaic Announcement

- NYC HPD — 388 Hudson Street RFP Process

- The Pritzker Architecture Prize — Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron (2001)

.jpeg)

-Compliance-for-NYC-Multifamily-%26-Co-Op-Facades.jpg)

_format(webp).avif)

_format(webp)%20(6).avif)

_format(webp)%20(5).avif)

_format(webp)%20(4).avif)

_format(webp)%20(2).avif)

_format(webp)%20(3).avif)

.avif)

_format(webp)%20(2).avif)